How I Had to Interpret a Photography Brief

Editorial shoots rarely arrive fully formed.

Sometimes there is no brief. No layout. No promise of how the images will ultimately be used.

This shoot was one of those days.

The models came from agencies outside London. A stylist, a makeup artist, and an assistant were present. The location had character, but it offered no guarantees. Nothing was neutral. Nothing was forgiving.

On paper, the task was simple and demanding at the same time. Create a cohesive set of images. Eight looks. Limited hours. One space. The margin for error was narrow.

For photographers, this is the moment where uncertainty either sharpens decision-making or paralyses it. What followed was not a technical exercise. It was a test of judgement.

Working Without a Brief Forces Better Decisions

When there is no fixed creative direction, photographers tend to do one of two things. They either hesitate or they lead.

In situations like this, I rely heavily on internal reference points. Past work. Visual memory. An instinctive understanding of how light behaves in space. These are not conscious calculations. They are accumulated responses.

This matters because most photographers wait for certainty before committing. In reality, certainty rarely arrives. The ability to lead without it is what separates competence from authority.

Rather than inventing ideas in isolation, I let the location speak first. Individual rooms dictated mood. Textures suggested contrast. Light falloff determined pacing and distance. The environment set the parameters.

For photographers, this is a reminder that locations are not backdrops. They are collaborators. Ignoring them usually results in images that feel imposed rather than resolved.

The strongest locations were identified early. Not because they were dramatic, but because they offered control. Control allows consistency. Consistency allows decisions to compound rather than fragment.

Why I Chose One Light. Deliberately.

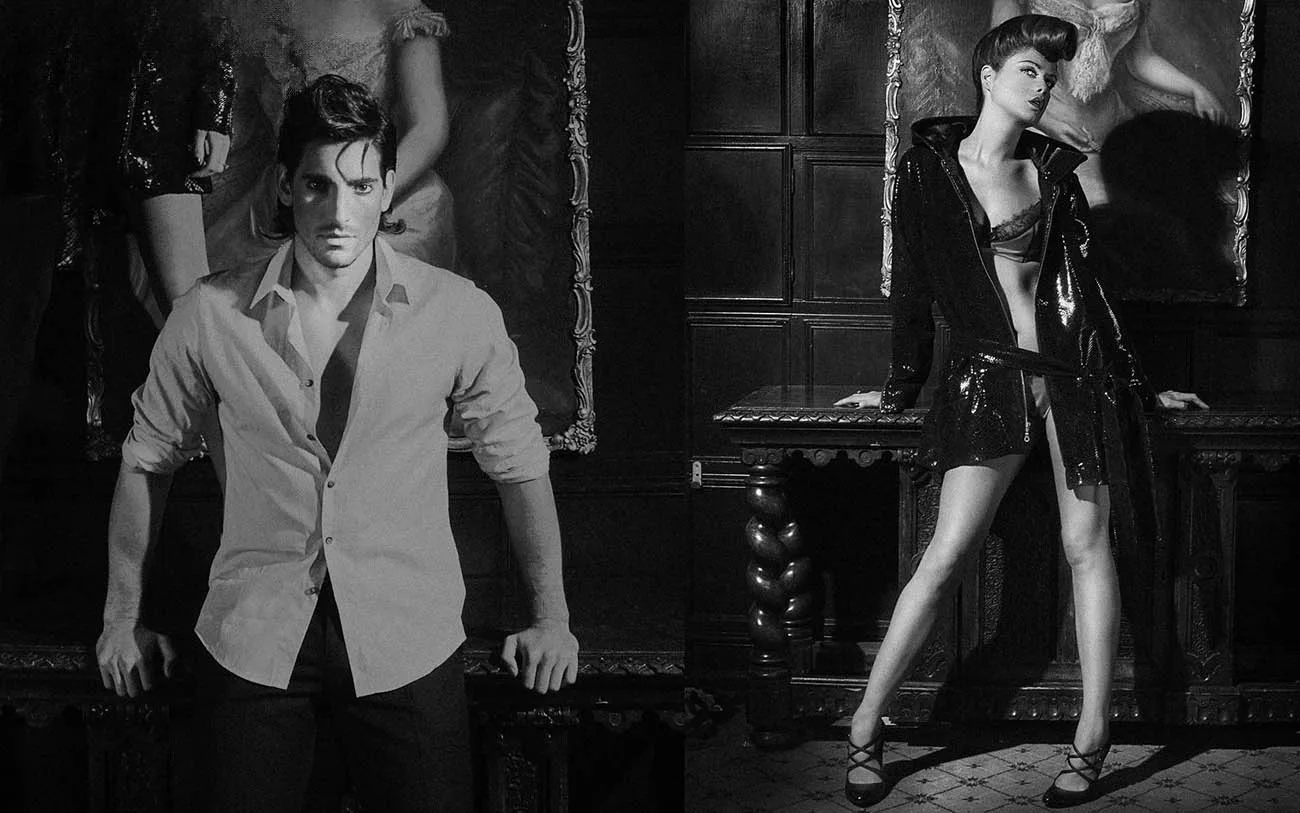

The entire shoot was lit with a single light by design.

Not because of limitation. Because discipline matters.

One light removes choice. It establishes a baseline that everything must work within. A single Rembrandt-style source creates shape without excess, drama without clutter, and continuity across multiple looks.

For photographers, this is where confidence shows. Multiple lights can hide indecision. One light exposes it. When the lighting is simple, the responsibility shifts back to timing, direction, and framing.

More lights introduce hesitation. They slow the process and encourage adjustment rather than commitment. One light forces decisions to be made quickly and defended in the moment.

Under time pressure, that discipline becomes essential.

Direction Beats Lighting Every Time

The aesthetic was led both visually and verbally throughout the day.

Clear direction matters. I adjusted posture, expression, and physical tension in real time. The aim was not performance, but presence. Allowing the model to react rather than pose created far stronger results than any technical refinement.

For photographers, this is often the missing skill. Lighting can be learned quickly. Direction cannot. Images fail more often from weak communication than from imperfect exposure.

Most of the final images came from interaction, not setup.

Input from the stylist and assistant was welcomed at key moments, particularly when it sharpened intent. But visual direction remained centralised. That clarity kept the shoot moving and prevented drift when time became tight.

This is what keeps a shoot from becoming a negotiation rather than a collaboration.

Time Pressure Changes Everything

Time can either constrain a shoot or focus it.

Here, the clock mattered. Eight looks meant that early decisions had to hold. There was no luxury of constant reinvention or endless refinement. Initial concepts were committed to, with only on-the-fly adjustments where absolutely necessary.

For photographers, this is uncomfortable but revealing. Time pressure exposes habits quickly. It shows whether decisions are instinctive or still being negotiated internally.

This is where many photographers lose control. They over-light. They over-adjust. They under-direct. The result is visual noise and diluted intent.

Pressure does not create problems. It reveals them.

What This Shoot Taught Me. And Still Does.

This image reinforced a principle I return to constantly.

Keep it simple. Trust interaction. Let restraint do the work.

Photographers often compensate for uncertainty with equipment. More lights. More modifiers. More complexity. The result is usually over-lit images and underwhelming direction.

For photographers reading this, the takeaway is uncomfortable but useful. The strongest work almost always comes from fewer variables, not more. Reduction sharpens judgement. It makes every decision visible. Including the weak ones.

Over time, working this way stripped colour out of my decision-making as well. Not stylistically, but structurally. Monochrome removed distraction and exposed form, light falloff, expression, and timing with nowhere to hide.

That way of seeing became disciplined enough to formalise. It is the foundation of my Monochrome Conversion course. Not as a preset-driven look, but as a system for training the eye to recognise what actually matters when excess is removed.

→ Explore the Monochrome Conversion course

A Note for Photographers in Similar Situations

If you find yourself working with a loose brief, limited time, multiple looks, and no clear visual endpoint, do less.

Choose one light. Commit early. Direct clearly.

Let the image come from interaction, not complexity.

This is not about style. It is about control.